In 2025, a curious paradox stands out in global housing: some of the world’s wealthiest and most advanced economies — including the UK, Canada and Australia — are now among the hardest places to buy a home. Prices have surged, supply has lagged and home-ownership has slipped out of reach for younger generations.

And yet, another wealthy, globally competitive nation with some of the tightest land constraints in the world — Singapore — has managed to keep home-ownership broadly attainable and widely distributed.

Why has this divergence happened? What explains why large nations with abundant land struggled, while a dense city-state succeeded?

This article explores that paradox. High national income alone does not guarantee housing affordability. Sustained accessibility depends on deliberate policy design, long-term discipline and housing systems that prioritise stability over short-term sentiment.

We compare the paths of the UK, Canada and Australia — where affordability pressures have intensified — with Singapore, where home-ownership rates remain among the highest in the world. From there, we distil key lessons for the future.

When Wealth Doesn’t Buy Affordability

One might expect that high-income economies should be better placed to provide affordable housing: higher wages, stronger institutions, better infrastructure. Yet the data show a very different pattern.

The paradox is clear: being a wealthy country or having high GDP per capita does not guarantee affordable housing. Instead, it appears that structural design of the housing system, regulatory levers and supply mechanisms matter more.

Why the UK, Canada & Australia Fell Into Crisis

Let’s examine how the “rich country first” affordability problem unfolded in three major economies.

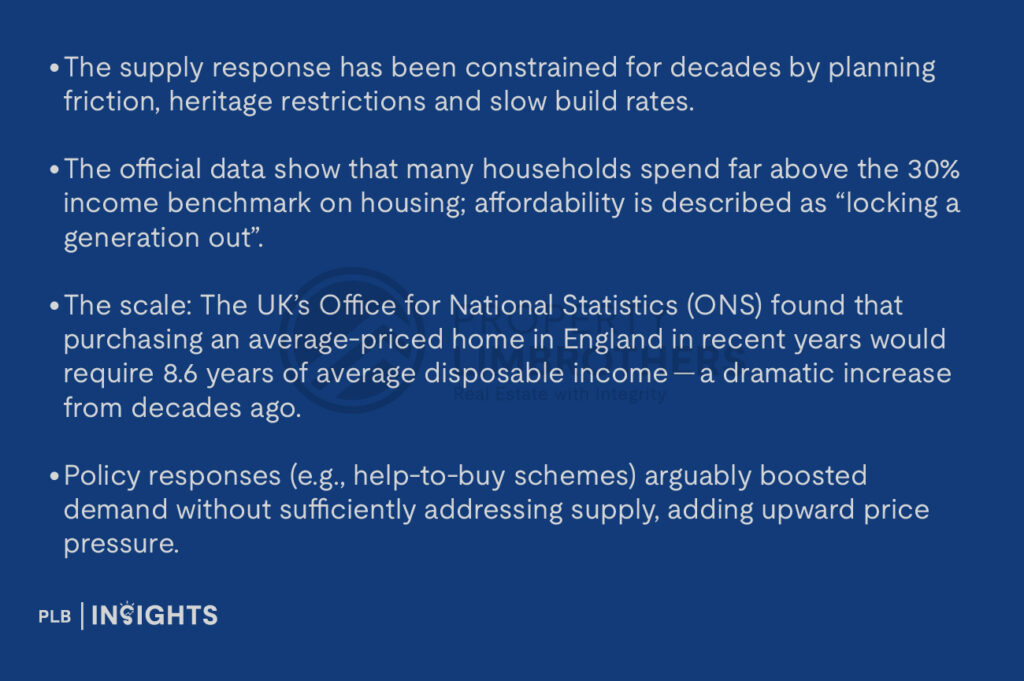

United Kingdom

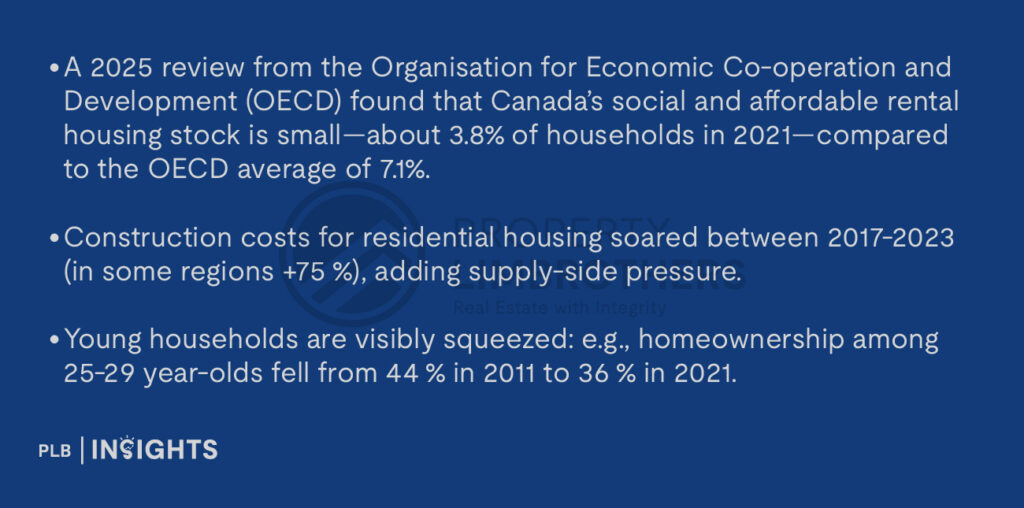

Canada

Australia

Common themes across all three

These countries show that when high incomes, strong aspirations for home ownership, easy access to credit and weak supply planning come together, affordability can break down much faster than expected.

Singapore’s Contrarian Design — From Scarcity to Stability

By contrast, Singapore’s outcome stands out: high home-ownership, relatively controlled affordability (in global comparison) and a system designed for resilience. Key pillars:

Public-housing backbone

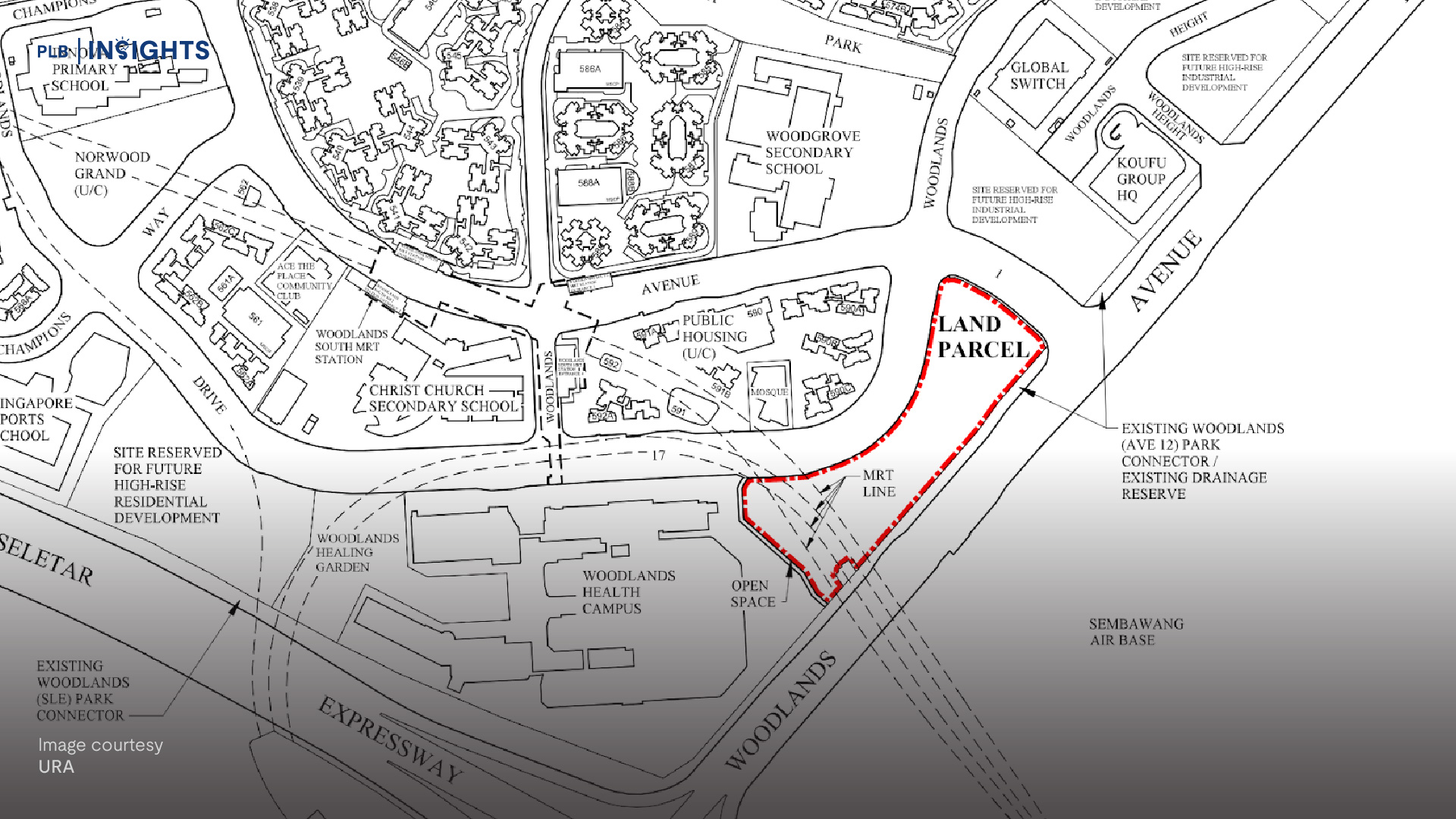

Strong land-use and supply planning

Demand management and owner-occupier prioritisation

Relative affordability

Culture of ownership & retirement-saving alignment

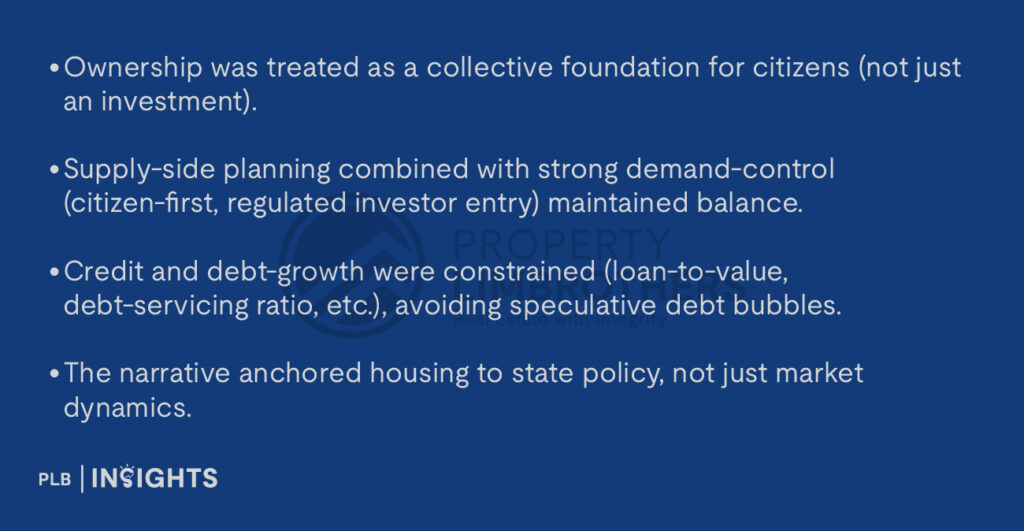

In short: Singapore didn’t rely on the market to self-correct. It engineered high ownership and controlled affordability through system design.

Why Other Countries Hit the Wall First — and Singapore Didn’t

Putting it together, the story becomes one of structural design and policy discipline.

Where Other Advanced Economies Struggled

Why Scarcity Became Singapore’s Advantage, Not a Weakness

In other words: Wealth without careful planning can create instability, while land scarcity paired with deliberate design and discipline builds long-term resilience.

What Singapore Still Needs to Watch

We are not immune to pressures. The stable outcome is an achievement — but not a guarantee.

Middle-income squeeze

As private housing prices continue to climb, middle-income households may face affordability headwinds even in Singapore. The system must remain responsive.

Global flows and private segment risk

Investor sentiment, global capital flows and private housing price momentum can still test the system’s buffers. Continued vigilance remains essential.

Right-sizing, ageing population & household size decline

The average household size is shrinking (3.09 persons in 2024) and demographic change is coming. The housing delivery model must adjust to smaller households and ageing residents.

Affordability perception & sub-markets

While the broader numbers look healthy, some segments (premium private condos, landed homes) may become out of reach for many. Managing market stratification remains important.

Sustaining supply discipline

Even with managed land, the interplay of supply, cost inflation (labour, materials) and global shocks (pandemic, supply-chain) could test housing delivery if unaddressed.

Final Perspective: Deliberate, Not Lucky

The key lesson for policymakers, developers and homeowners is clear: housing resilience is not something that happens by chance. Singapore’s ability to sustain high home-ownership and relative affordability is the result of decades of intentional design and discipline.

In many advanced economies, market forces and rising incomes were expected to support affordability — until they didn’t. The housing challenges we see across developed markets today are less about wealth constraints and more about the absence of long-term structural planning.

For us at PropertyLim Brothers, one point stands out: system design matters. Beyond site, layout or transaction strategy, it is the broader policy infrastructure — land-release planning, financing rules, demand controls and long-term governance — that shapes housing stability.

Owning a home should not hinge on timing or luck. It should be guided by a framework that balances aspiration, accessibility and stability across generations.

For buyers in Singapore, the takeaway is simple: look beyond prices and headlines. Consider the system behind the market, how supply is planned, and how demand is managed. Even in a high-income, land-scarce nation, long-term stability is possible when the fundamentals are sound.

As you plan your next move in the Singapore property market, our team is here to help you navigate options with clarity and confidence. Click here to connect with our sales consultants.