As global financial conditions shift, many investors wonder: Does Singapore’s property cycle move in tandem with the global liquidity cycle? Or does it lag behind?

The short answer? Yes, it typically lags, and there are multiple layers of why this happens—especially in a tightly managed market like Singapore’s.

Understanding the Lag: Why It Happens

Delayed Transmission Mechanism

Global liquidity—defined by the availability and cost of capital—is largely driven by central bank actions like interest rate changes or quantitative easing/tightening. However, it takes time for these shifts to ripple through the economy and affect consumer borrowing behaviour.

When interest rates are cut, for instance, banks don’t always immediately lower mortgage rates. Even when they do, it takes time for buyers to react, secure loans, and complete property transactions.

Market Inertia in Real Estate

Unlike equities or crypto markets that respond almost instantly to macroeconomic shifts, property markets operate with natural friction. Buyers take weeks or months to make decisions; transactions take even longer to conclude. This built-in inertia means that even if global liquidity loosens, the property market doesn’t move in lockstep.

Government Cooling Measures

Perhaps the biggest reason for the lag in Singapore’s property market is policy intervention. The government has consistently introduced cooling measures—most recently, the April 2023 ABSD hike, which doubled the Additional Buyer’s Stamp Duty for foreign buyers from 30% to 60%.

These measures deliberately moderate demand, especially from speculative or foreign investors, thereby decoupling Singapore’s property cycle from global liquidity to some extent. In essence, even if the global money tap is turned on, Singapore puts a regulator on that tap.

Economic and Psychological Factors

Beyond interest rates and liquidity, sentiment plays a big role. In uncertain times, even with cheap money available, buyers may hold back due to fears of job instability or price corrections. This behavioural dynamic adds yet another layer of lag.

Singapore in Context: Expansion vs Contraction

During Expansionary Liquidity Cycles:

When global central banks ease monetary policy (like during COVID-19), Singapore’s property market doesn’t always immediately spike.

Example: After liquidity surged post-COVID in 2020, Singapore’s property market only saw a significant rebound in 2021–2022. That’s a one- to two-year delay, largely attributed to buyer caution and the dampening effects of existing policies.

During Contractionary Phases:

Conversely, when liquidity tightens and rates rise, Singapore’s property market tends to stay resilient initially, then gradually cools as financing becomes costlier. The delay again is due to buyers’ ability to lock in earlier, lower rates and the typically long lead time in property decision-making.

The 2023 ABSD hike serves as a perfect example—despite liquidity still being relatively high at the time, foreign buying cooled rapidly, illustrating how targeted policies can override liquidity cycles.

The Trump Tariff Factor: A Wildcard in the Liquidity-Property Link

Looking ahead, one must not ignore geopolitical shocks—and the biggest wildcard right now is Trump’s return and his tariff policy.

In early 2025, he reintroduced sweeping tariffs, triggering immediate global market volatility. Though he has since announced a 90-day pause and moderated most tariffs to 10%, Chinese imports still face a staggering 125% duty.

What happens after this 90-day window is critical. If Trump reinstates higher tariffs across the board, we could see:

These ripple effects can tighten global liquidity, especially in export-heavy economies like Singapore. If capital flows reverse and interest rates remain high for longer, this may delay any expected rebound in property activity, especially in the high-end and luxury sectors dependent on foreign demand.

In short, Trump’s tariff policies can indirectly prolong the contractionary liquidity phase, meaning Singapore’s property market may take even longer to pick up steam—especially if further cooling measures are implemented in anticipation of capital inflows.

Key Takeaway

Singapore’s property cycle does lag behind the global liquidity cycle—and this lag is not accidental. It’s a result of:

As such, monitoring global liquidity alone is not enough. To anticipate property market movements here, one must also track local policies, buyer sentiment, and regulatory signals.

Bonus for You: Visualising the Lag

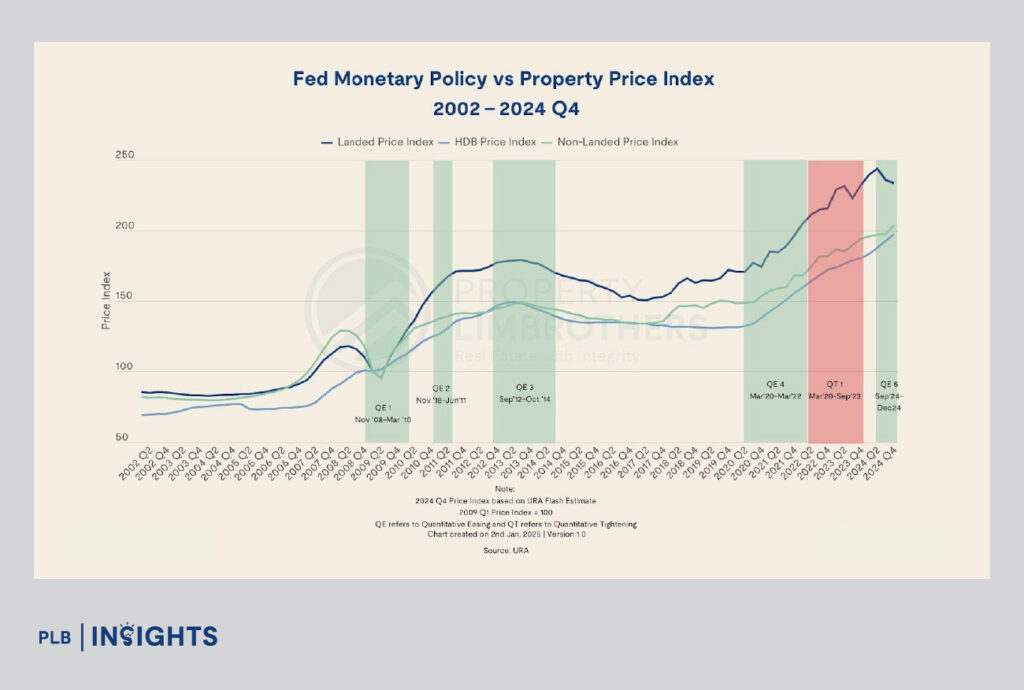

To help visualise the relationship between global liquidity and Singapore’s property market, we’ve included a Fed Monetary Policy vs Property Price Index chart (2002 – 2024 Q4). This chart tracks how HDB, non-landed, and landed home prices have moved across key liquidity phases—Quantitative Easing (QE) and Quantitative Tightening (QT).

Quantitative Easing: When central banks inject money into the economy by purchasing financial assets, making it easier and cheaper for people and businesses to borrow and spend.

Quantitative Tightening: When central banks reduce money in the economy by selling financial assets or letting them mature, making borrowing more expensive to control inflation and slow spending.

What the Chart Shows:

This chart reinforces the key takeaway: Singapore’s property market doesn’t react immediately to global liquidity. It absorbs and reflects those shifts slowly, shaped by local fundamentals, buyer psychology, and policy measures.

Looking to make your next move with greater confidence? Whether you’re buying, selling, or simply exploring your options, understanding how global liquidity cycles affect local prices can give you a sharper edge. Reach out directly to our expert consultants for personalised guidance on timing your property decisions.