Executive condominiums (ECs) hold a unique appeal among Singaporeans, especially for those looking to upgrade from an HDB flat or enter the property market with their first home. Due to the eligibility criteria and income ceiling, many buyers can leverage government grants to make ECs more affordable, further fuelling their popularity. As a hybrid between public and private housing, ECs offer the allure of private housing standards with the price accessibility of subsidised flats—an attractive proposition for many.

There’s a common perception that purchasing an HDB flat or EC is a “sure-win” investment, backed by the logic that Singapore’s limited land and steady housing demand will drive up prices. This belief is so ingrained that many buyers assume that selling at a profit is almost a guarantee. The scarcity of land and the government’s commitment to maintaining housing affordability seem to reinforce this perspective, fostering a sense of security around EC investments.

However, few buyers consider the possibility of a loss, particularly in EC transactions. With high expectations, some buyers might overextend their finances, aiming to secure a larger property or a more luxurious unit. This tendency toward over-leveraging places them in precarious financial positions, especially when the market turns bearish or economic conditions weaken. In such situations, factors like rising interest rates, layoffs, or financial downturns can quickly erode their ability to hold onto these properties, pushing them to sell at a loss.

We’ll delve into the surprising reality that some executive condominium (EC) transactions in Singapore haven’t been the “sure-win” investments many people expect. While ECs are often seen as a stable step up from HDB flats, there are instances where buyers face real financial losses. Many of these cases involve buyers who may have been drawn in by the appeal of a larger or more premium property but overextended financially to secure it. When buyers stretch their finances too thin, they are left vulnerable to market downturns or unexpected economic setbacks, like unemployment. In such situations, they may be forced into “distress sales”—selling the property quickly and often below market value—just to recover some of their investment, even if it means taking a loss.

To uncover why some ECs underperform, we’ll start with an exploration of specific properties that didn’t fare well in the market. This first section, “Bad Property Picks? HODL or Lose,” will highlight the factors that have driven down prices for certain ECs. By looking at a variety of cases, we’ll see how market conditions, location, surrounding infrastructure, and buyer choices all play into whether an EC purchase results in profit or loss.

The analysis continues with “A Deep Dive into the Top 3 Unprofitable ECs,” where we’ll examine the particular EC projects that have recorded the largest financial losses. We’ll assess each project individually to better understand the reasons behind these outcomes, considering factors such as location-specific oversupply, shifts in buyer demand, and unique characteristics that have affected these properties’ values. This deep dive will reveal how even small, overlooked elements can significantly impact the investment potential of ECs.

Finally, we’ll place these cases within a broader historical context by revisiting market dynamics from the mid-2000s. In “What Happened in 2004 and 2005 in Singapore?” We’ll look at how economic shifts and policy changes from those years influenced property prices, creating patterns that resonate with today’s market. These historical insights may help current and prospective buyers make more informed decisions by understanding what factors might affect EC values going forward, offering key lessons in navigating a fluctuating property market.

To help current EC owners make informed decisions, we’ve also prepared an in-depth report on a crucial question many face: Should you sell your EC as soon as it meets the Minimum Occupation Period (MOP), or hold out for potentially greater gains? Our report evaluates market trends, past performance, and financial considerations to guide owners on the timing and strategy of selling. Dive into the full analysis and discover whether holding or selling could better align with your financial goals—access the report through the link here!

Bad Property Picks? HODL or Lose

The saying “time in the market beats timing the market” holds especially true for property, yet not everyone is fortunate enough to select the top-performing properties. In cases where an EC investment falls short of expectations, time often becomes the most effective ally. Financial stress, rising opportunity costs, or market fluctuations, however, can pressure owners into “panic selling,” which can lead to suboptimal outcomes.

Our report reveals a telling trend: almost no EC transactions show losses if owners hold onto their properties for at least six years beyond the Minimum Occupation Period (MOP). Yet, a significant proportion of losses do occur within the first zero to three years post-MOP, highlighting that patience and a long-term outlook can be pivotal in maximising returns—or minimising losses—on EC investments.

The data in this table reveals significant trends in the profitability of EC transactions based on the length of time units are held after the Minimum Occupation Period (MOP). For units sold within the first year post-MOP, 7.3% resulted in losses, indicating that this early period carries the highest risk for unprofitable sales. This risk continues to be elevated through the first three years post-MOP, where loss percentages peak sharply at 20.1% in the 1-2 year range and remain above 6% in the 2-3 year range. These figures suggest that selling immediately after the MOP can be risky for owners who hope to avoid losses.

As the holding period lengthens, the proportion of units sold at a loss declines significantly. By the 4-6 year mark, loss percentages drop to well below 5%, showing a clear advantage for owners who are able to hold their properties through potential market fluctuations and personal financial challenges. Beyond six years after MOP, loss rates continue to decline steadily. In fact, from the 12-year mark onward, the data indicates that no units were sold at a loss, suggesting that long-term holding almost entirely mitigates the risk of unprofitable transactions.

This analysis highlights a clear takeaway: time in the market is critical for EC owners seeking to maximise profitability or minimise potential losses. The drastic decrease in loss rates after the first few years post-MOP underscores the potential value of holding onto a property even in uncertain market conditions. For EC owners facing financial pressure or tempted to sell early, this data supports a strategic approach to timing their sale, especially if their goal is to avoid financial loss.

A Deep Dive into the Top 3 Unprofitable ECs

We’ll take a closer look at the specific executive condominiums (ECs) that have experienced the most significant losses among recent transactions. Although the broader data indicates that a long-term Hold Onto Dear Life (HODL) strategy can be effective in avoiding financial losses, this general approach may not be sufficient to address unique challenges faced by certain properties. Not all ECs perform equally well over time, and understanding why some projects struggle to retain value can offer valuable insights for prospective buyers and current owners alike. By analysing these outliers, we can uncover factors that contribute to unprofitable outcomes and identify warning signs to look out for when assessing EC investments.

To deepen our understanding of why some executive condominiums (ECs) perform poorly despite the broader HODL strategy, let’s analyse the top three ECs with the highest percentage of units sold at a loss. From the data, it’s clear that certain projects stand out for their high proportion of unprofitable transactions. In this section, we’ll look specifically at Simei Green Condominium, Westmere, and Yew Mei Green, each of which has struggled in the resale market despite the general resilience of ECs over time. By examining these specific cases, we can better understand what factors may lead to financial losses and how these insights might help prospective buyers make informed decisions.

Simei Green Condominium (36.7% of units sold at a loss)

Simei Green tops the list with a notable 36.7% of its units sold at a loss. This EC, with its Minimum Occupation Period (MOP) met in 2004, has faced unique challenges over the years. Located in the eastern part of Singapore, it may be affected by factors such as limited amenities or competition from newer developments in more accessible or developed areas. Despite its mature estate setting, which often appeals to families, the project has struggled to retain value for some owners. Buyers seeking ECs might interpret this as a signal to carefully assess the amenities and development plans in the surrounding area before purchase. Simei Green’s performance also highlights the importance of evaluating the impact of competing developments, as older properties may lose appeal when buyers have newer alternatives.

Westmere (33.0% of units sold at a loss)

Located in Jurong East, Westmere follows closely behind with 33.0% of its units sold at a loss. This EC, which reached its MOP in 2004, is situated in a region that has since seen substantial growth, especially with the development of the Jurong Lake District. However, Westmere’s lacklustre resale performance may reflect certain drawbacks, such as less favourable unit layouts, ageing facilities, or a lower demand for resale units due to newer projects nearby. Despite being in an area with considerable long-term development potential, Westmere’s case illustrates that even well-located ECs are not immune to depreciation if they do not evolve to meet shifting market expectations. This is an important takeaway for buyers who may be banking on future growth in developing areas; not all properties will benefit equally from district-wide improvements.

Yew Mei Green (30.3% of units sold at a loss)

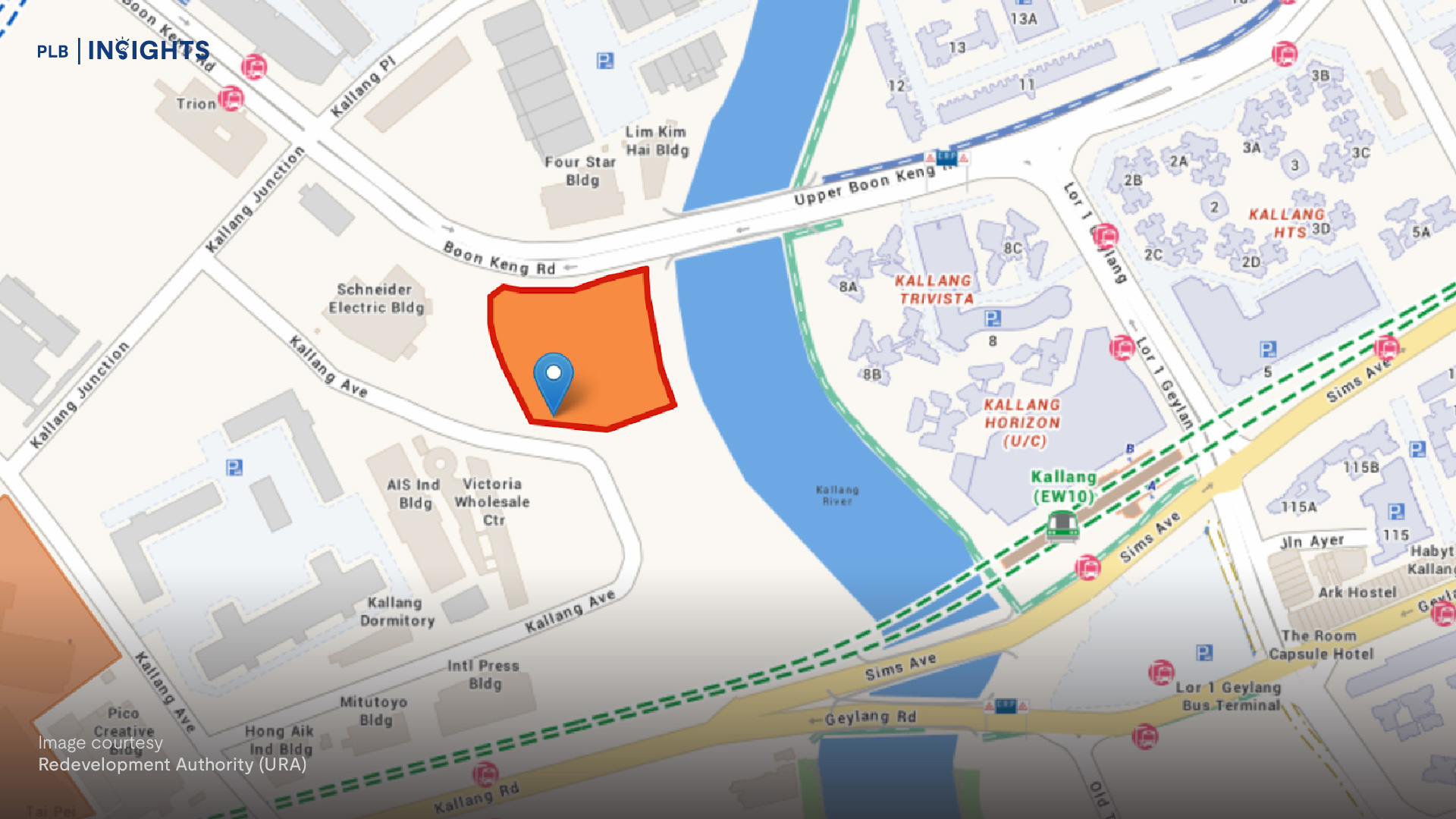

Yew Mei Green, which reached its MOP in 2005, is another project with a high percentage of unprofitable transactions at 30.3%. Situated in Choa Chu Kang, this EC might be impacted by its location on the city’s fringe, where accessibility to central business districts is relatively limited compared to other ECs. Additionally, older properties like Yew Mei Green may suffer from depreciation due to wear and tear, higher maintenance costs, or a lack of nearby amenities that newer ECs or private condominiums offer. This project serves as a reminder for buyers to consider both the current and future appeal of a property’s location, as fringe developments may have less robust demand, particularly if connectivity improvements or new infrastructure do not materialise as anticipated.

These top three cases underscore how timing and location can impact the financial outcomes of EC investments. While Simei, Jurong East, and Choa Chu Kang are now considered decent locations with matured amenities and ongoing development, this was not the case two decades ago. Back then, these developments in the Outside Central Region (OCR) faced limited amenities and had to contend with ongoing construction of newer projects in the surrounding areas, which temporarily suppressed demand and resale values. The losses incurred by early sellers reflect missed opportunities, as they sold before the full potential of these areas was realised. For owners who waited, or those who held through these transitional years, the value of their properties likely benefited as these regions became more developed and accessible, making a strong case for a patient, long-term approach to EC ownership in maturing neighbourhoods.

What happened in 2004 and 2005 in Singapore?

The years 2004 and 2005 marked a pivotal period in Singapore’s real estate market, particularly for Executive Condominiums (ECs) in developing neighbourhoods. In those years, the Singapore economy was in recovery mode after the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s, which had led to economic uncertainty and impacted consumer confidence. This was further compounded by the SARS outbreak in 2003, which dampened economic growth and caused property prices to stagnate or even fall in certain areas. As a result, many EC developments in Outside Central Region (OCR) areas like Jurong East, Choa Chu Kang, and Simei—now bustling neighbourhoods—were still relatively underdeveloped and lacked the amenities and infrastructure that residents today might take for granted.

During this period, the OCR areas faced significant competitive pressures. Developers continued building new ECs and private condominiums nearby, which introduced additional supply and delayed the appreciation of existing EC properties. Unlike the well-established neighbourhoods in the Central Region, OCR areas were still evolving, with limited public transport options, fewer shopping malls, and a shortage of quality schools and recreational facilities. The combination of these factors meant that the value of ECs in these regions did not increase as expected, leaving early owners disappointed and some facing financial losses if they needed to sell shortly after the Minimum Occupation Period (MOP).

In the two decades since, however, these neighbourhoods have transformed dramatically, with each area seeing substantial infrastructure and lifestyle improvements. Jurong East, for example, is now a vibrant regional hub with major shopping centres like Westgate, JEM, and IMM, as well as new healthcare facilities and educational institutions. Simei has benefited from the growth of Tampines and the presence of Changi Business Park, which have both enhanced employment opportunities and increased the demand for residential housing in the vicinity. Choa Chu Kang, while initially perceived as distant from central areas, now has improved connectivity due to MRT and bus networks, and benefits from renovated projects like Lot One Shoppers’ Mall.

Another major factor contributing to the subsequent increase in property values in these neighbourhoods has been the government’s sustained commitment to decentralisation through the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) Master Plan. The URA’s strategy to develop regional centres like Jurong and Tampines brought more jobs and amenities closer to these OCR areas, making them more desirable places to live over time. These developments attracted more buyers and boosted the resale market for ECs. Unfortunately, owners who sold soon after MOP missed out on these long-term gains, as their properties only realised higher valuations years after these improvements took shape.

The economic environment of the early 2000s presented challenges that created unprofitable outcomes for some early EC owners, but it also underscores a broader lesson on the importance of timing and patience in property investment. Those who held onto their ECs during these initial years of uncertainty were eventually rewarded as their neighbourhoods grew and amenities improved. This trend of neighbourhood maturation and property value appreciation serves as a reminder that OCR properties, while not immediately lucrative, can yield significant returns over time as they transition into fully-developed communities.

In Conclusion

Ultimately, the story of these unprofitable EC transactions in 2004 and 2005 highlights the interplay between economic conditions, policy changes, and regional development. The ECs that struggled to appreciate in the past are now in areas benefiting from decades of consistent development and strategic planning. For today’s buyers, these cases provide valuable insight into how property value evolves in tandem with economic cycles and infrastructural growth, reinforcing the idea that long-term investment strategies may be the key to maximising returns in Singapore’s real estate market.

Have more questions about navigating the EC market in the current landscape? Do reach out to our team of experienced consultants here and we’ll be glad to advise with personalised consultations for your property journey. As always, see you in the next one.